KNEECAP, Protest & Palestine

On the eve of Liam Ó hAnnaidh’s (Mo Chara’s) court case in London, we stand at a crossroads for music, protest, Palestine and the relationship between Ireland and the United Kingdom.

Palestine and protest are inseparable in British politics today. Last month’s ban on Palestine Action and its designation as a terrorist organisation under the Terrorism Act sparked widespread demonstrations and arrests: 474 in London, 13 in Norwich and 1 in Belfast. The London protest, the largest since the ban, saw Irish citizens among those detained, including Limerick’s Sinéad Ní Shiacáis. The charges mirror those now faced by Mo Chara.

Protesters in London last weekend. Photograph: Tolga Akmen/EPA

Ireland’s support for Palestine runs deep. It has been visible through artists like KNEECAP but also in the literary world, most notably in Sally Rooney’s recent Irish Times article. The novelist condemned the Irish government’s inaction and highlighted the hypocrisy of Britain’s shifting definition of “terrorism” depending on political convenience. Rooney contrasted the arrests of Palestine Action activists with the rebuilding of a loyalist UVF mural in Belfast, noting that while the UVF remains a proscribed organisation responsible for hundreds of civilian deaths, its public glorification has gone unchallenged. Palestine Action, by contrast, has caused no deaths and never advocated violence. Rooney pledged to donate her royalties, including from Normal People, to Palestine Action. “If this makes me a supporter of terror under UK law,” she wrote, “so be it.”

This is not new ground for the Irish. Branded “terrorists” for their own fight for independence, Ireland’s writers and musicians are acutely aware of how language is used to mask colonial violence.

Sally Rooney: 'The ramifications for cultural and intellectual life in the UK will be profound'

Shared Histories

The question arises: why are Irish people so invested in Palestine? The answer lies in shared history. The methods Britain used in Ireland were often exported to the Middle East. David Cronin highlighted this in the Irish Times, noting that Arthur James Balfour, author of the Balfour Declaration, earned the nickname “Bloody Balfour” for ordering police to fire on land reform protesters in Mitchelstown, Co Cork in 1887. Three died. Later, as Home Secretary, Herbert Samuel oversaw the internment of thousands after the Easter Rising before becoming Britain’s first High Commissioner of Palestine.

Arthur Balfour addresses an anti Home-Rule demonstration in Belfast in 1893. Photograph:

Getty Images

Colonial administrators drew their own parallels. Ronald Storrs, Military Governor of Jerusalem, wrote in 1937 that the aim of the Balfour Declaration was to create a “little loyal Jewish Ulster in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism.”

Famine or Starvation?

Language again matters. The BBC has described the current situation in Gaza as “famine.” Yet famine implies natural disaster. What is happening in Gaza is deliberate starvation. UN-backed experts warn that food is being withheld, with more than 60 requests to deliver aid denied in July alone. Over 100 organisations have called on Israel to end the weaponisation of food.

For the Irish, this resonates deeply. Under British rule, Ireland’s Great Hunger is often labelled a famine. Many reject the term, pointing to how food continued to be exported while people starved. British newspapers of the time called the catastrophe a punishment for rebellion. The (London) Gazette in 1847 spoke of “famine and pestilence” teaching the Irish “wisdom,” while The Yorkshireman sneered in 1848 that England would “be the gainer” if the Irish were left to starve. These narratives echo today’s evasions in British media about Gaza.

Kneecap and the Art of Protest

Into this historical current step Kneecap. In 2024 the group won a legal battle against the British government after funding was unlawfully withheld. Now Mo Chara faces terrorism charges for allegedly displaying a Hezbollah flag at a London concert.

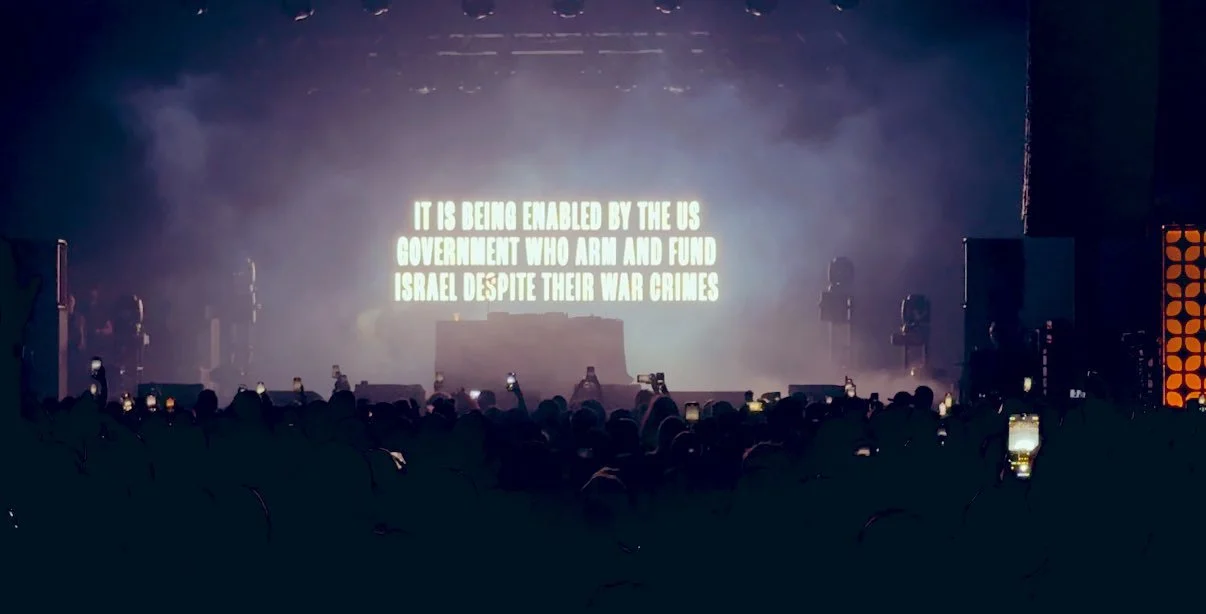

The charges come on the heels of Kneecap’s Coachella performance where they denounced Israel’s actions in Gaza and accused the US of complicity. At Glastonbury, they performed despite the Prime Minister’s objections, leading to their set being pulled from live broadcast. Mo Chara told the crowd that while Kneecap feel the weight of state pressure, it pales beside what Palestinians endure: “Kids being starved to death in this day and age... Israel are war criminals. It’s a genocide.”

Prior to the initial June court hearing, Kneecap’s PR campaign, “More Blacks, More Dogs, Mo Chara,” deliberately evoked racist signs once common in London, a history the BBC and Telegraph attempted to dismiss but which Irish emigrants recall vividly. The campaign drew attention to the parallels between historic anti-Irish discrimination and today’s political repression. The group has since been banned from advertising in the London Underground.

During that June court date, Mo Chara’s request for an Irish language translator in court only underlined those tensions. Laughter broke out when the magistrate claimed none could be found, bandmate DJ Próvaí stepped in, echoing Kneecap’s own BAFTA-winning film. If granted, it would be the first use of Irish in a British court for nearly 300 years, reversing the legacy of the Penal Laws that sought to erase the language.

A Test Case

Mo Chara’s trial is about more than one rapper. It is a test case for how Britain deals with dissent and with Irish voices of solidarity for Palestine. A 14-year sentence is possible. Such an outcome would be seen as an attack on civil liberties in Britain and as another example of anti-Irish, anti-Palestine discrimination. Yet dropping the charges would embarrass the government and validate Kneecap’s defiance. A minor penalty may be the state’s safest option.

Either way, this case has already become a touchstone. It connects Ireland’s history of colonial repression to Palestine’s present struggle and reminds us of the enduring power of protest music to speak truths states would rather silence.